:focal(713x327:714x328)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fe/f8/fef899d3-ffbc-41de-8ebe-9e8f807ec361/testing.jpg)

Houdini exposed fake Spiritualist practices by having himself photographed with the "ghost" of Abraham Lincoln.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Harry Houdini was just 52 when he died on Halloween in 1926, succumbing to peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix. Famous in life for his improbable escapes from physical constraints, the illusionist promised his wife, Bess, that—if at all possible—he would also slip the shackles of death to send her a coded message from the beyond. Over the next ten years, Bess hosted annual séances to see if the so-called Handcuff King would come through with an encore performance from the spirit world. But on Halloween 1936, she finally gave up, declaring to the world, “Houdini did not come through. ... I do not believe that Houdini can come back to me, or to anyone.”

Despite Bess’ lack of success, the Houdini séance ritual persists to this day. Though visitors are banned from visiting the magician’s grave on Halloween, devotees continue to gather for the tradition elsewhere. Ever the attention-seeker in life, Houdini would be honored that admirers are still marking the anniversary of his death after 95 years. He’d likely be mortified, however, to learn that these remembrances take the form of a séance.

In the last years of his life, Houdini, who’d once displayed open curiosity about Spiritualism (a religious movement based on the belief that the dead could interact with the living), publicly inveighed against fraudulent mediums who conned grieving customers out of their money. A few months before his death, Houdini even testified before Congress in support of legislation that would have criminalized fortune-telling for hire and “any person pretending to … unite the separated” in the District of Columbia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2e/02/2e02246e-0def-44d1-a832-fe63bc60e359/2560px-harry_houdini__senator_capper_senate_district_com_2-26-26_lccn2016850832.jpg)

Harry Houdini (seated at center left) with Senator Arthur Capper (right) at a 1926 congressional hearing

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Described by the Washington Post as “uproarious,” the 1926 congressional hearings marked the culmination of Houdini’s all-consuming mission to put fake mediums out of business. At the outset, the magician stated his case plainly: “This thing they call Spiritualism, wherein a medium intercommunicates with the dead, is a fraud from start to finish.”

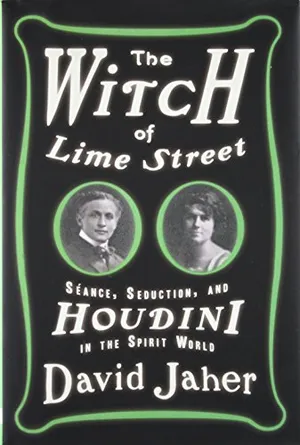

“[These hearings were] the apex of Houdini’s anti-Spiritualist crusade,” says David Jaher, author of The Witch of Lime Street, a 2015 book about Houdini’s yearlong campaign to expose a Boston medium as a fraud. “This [work] is what he wanted to be remembered for. He did not want to go down in history as a magician or an escape artist.”

For Houdini, a man who’d made a living suspending disbelief with skillful, innovative illusions, Spiritualist mediums transgressed both the ethos and artistry of his craft. Houdini rejected others’ claims that he himself possessed supernatural powers, preferring the label of “mysterious entertainer.” He scoffed at those who professed psychic gifts yet performed their tricks in the dark, where, as further insult to his profession, “it is not necessary for the medium to be even a clever conjurer.”

Worse still was the violation of trust, as the troubled or grief-stricken viewer never learned that the spirit manifestations were all hocus-pocus. Houdini had more respect for the highway robber, who at least had the courage to prey upon victims out in the open. In trying to expose frauds, however, the magician ran up against claims that he was infringing upon religion—a response that illuminates rising tensions in 1920s America, where people increasingly turned to science and rationalist thought to explain life’s mysteries. Involving leading figures of the era, from Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle to inventor Thomas Edison, the ramifications of this clash between science and faith can still be felt today.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6d/e1/6de1126b-513f-40b5-a491-0928a48f7c59/houdini_displays_tricks_of_fraudulent_mediums.jpeg)

Houdini (seated at left) exposes fraudulent psychics' tricks in a 1925 demonstration.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Spiritualism’s roots lay in 1840s New York: specifically, the Hydesville home of the Fox sisters, who adroitly cracked their toe knuckles to fool their mother, then neighbors and then the world that these disembodied raps were otherworldly messages. Over the next few decades, the movement gained traction, attracting followers of all stations. During the 1860s, when many Americans turned to Spiritualism amid the devastation of the Civil War, First Lady Mary Lincoln held séances in the White House to console herself following the death of her second-youngest son, Willie, from typhoid fever. Later first ladies also consulted soothsayers. Marcia Champney, a D.C.-based clairvoyant whose livelihood was threatened by the proposed 1926 legislation, boasted both Edith Wilson and Florence Harding as clients.

Even leading scientists believed in Spiritualism. The English physicist Sir Oliver Lodge, whose work was key to the development of the radio, was one of the chief purveyors of Spiritualism in the United States. Creator of the syntonic tuner, which allows radios to tune in specific frequencies, Lodge saw séances as a way of tuning in to messages from the spirit world. Edison and Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, similarly experimented with tools for spirit transmissions, viewing them as the next natural evolution of communication technology. As Jaher says, “The idea [was] that you could connect with people across the ocean, [so] why can’t you connect across the etheric field?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/29/76/29768de5-70b8-402c-b663-d81cb5baab77/gettyimages-515182284.jpg)

Houdini famously—and publicly—clashed with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, over the English writer's support of Spiritualism.

Getty Images

In 1920, Houdini befriended one of Spiritualism’s most ardent supporters, Conan Doyle. A medical doctor and the creator of Holmes, the most celebrated rationalist thinker in literature, Conan Doyle was also dubbed “the St. Paul of Spiritualism.” In the writer’s company, Houdini feigned more openness to Spiritualism than he truly possessed, holding his tongue during a séance in which Conan Doyle’s wife, Jean—a medium who claimed to be skilled in automatic writing—scribbled out a five-page message supposedly from Houdini’s dearly departed mother. (The magician once wrote that the crushing loss of his mother in 1913 set him on his single-minded search for a genuine spirit medium, but some Houdini experts argue otherwise.) After the session, Houdini privately concluded that Jean was not a true medium. His Jewish mother, the wife of a rabbi, would not have drawn a cross atop each page of a message to her son.

The pair’s friendship became strained as Houdini’s private opinion of Conan Doyle’s Spiritualist beliefs morphed into a public disagreement. The men spent years waging a cold war in the press; during lecture tours; and even before Congress, where Houdini’s opinion of Conan Doyle as “one of the greatest dupes” is preserved in a hearing transcript.

While Houdini, by his own estimate, investigated hundreds of Spiritualists over a 35-year span, his participation in one investigation dominated international headlines in the years prior to his trip to Washington. In 1924, at the behest of Conan Doyle, Scientific American offered a $2,500 prize to any medium who could produce physical manifestations of spirit communications under stringent test conditions. “Scientific American was a really big deal in those days. They were sort of the ‘60 Minutes’ of their time,” says Jaher. “They were investigative journalists. They unveiled a lot of hoaxes.” The magazine formed a jury of eminent scientific men, including psychologists, physicists and mathematicians from Harvard, MIT and other top institutions. The group also counted Houdini among its members “as a guarantee to the public that none of the tricks of his trade have been practiced upon the committee.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/73/9e/739ebe3d-fe11-42d2-a37d-8c4ad524c876/mina_crandon_with_harry_houdini.png)

Medium Margery Crandon (left) undergoing one of Houdini's (right) tests during the Scientific American investigation

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

After dismissing several contestants, the committee focused its attentions on upper-class Boston medium Margery Crandon, the wife of a Harvard-trained doctor. Her performance, if a deception, suggested a magician’s talent rivaling Houdini. While slumped in a trance, her hands controlled by others, Crandon channeled a spirit that reportedly whispered in the ears of séance sitters, pinched them, poked them, pulled their hair, floated roses under their noses, and even moved objects and furniture about the room.

The contest’s chief organizer, who Houdini criticized for being too cozy with Crandon, declined to invite the magician to the early séances, precisely because his tough scrutiny threatened to upset the symbiotic relationship between the medium and the jury. “She was very attractive and ... used her sexuality to flirt with men and disarm them,” says Joe Nickell, a onetime magician and Pinkerton agency detective who has enjoyed a fabled career as a paranormal investigator. “Houdini wasn’t fooled by her tricks. … [Still], she gave Houdini a run for his money.” Fearful that Scientific American would award Crandon the prize over his insistence she was a fraud, the magician preemptively issued a 40-page pamphlet titled Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by Boston Medium “Margery.” Ultimately, he convinced the magazine to deny Crandon the prize.

Houdini’s use of street smarts to hold America’s leading scientific authorities accountable inspired many of his followers to similarly debunk Spiritualism. Echoing Houdini’s declaration that “the more highly educated a man is along certain lines, the easier he is to dupe,” Remigius Weiss, a former Philadelphia medium and a witness supporting the illusionist at the congressional hearing, further explained the vulnerabilities of scientists’ thinking:

They have built up a sort of theory and they treasure it like the gardener with his flowers. When they come to these mediumistic séances, this theory is in their minds. … With a man like Mr. Houdini, a practical man who has ordinary common sense and science at his disposition, they cannot fool him. He is a scientist and a philosopher.

When he arrived in Washington for the congressional hearings, Houdini found a city steeped in Spiritualism. At a May 1926 hearing, Rose Mackenberg, a woman Houdini had employed to investigate and document the practices of local mediums, detailed an undercover visit to Spiritualist leader Jane B. Coates, testifying that the medium told her during a consultation that Houdini’s campaign was pointless. “Why try to fight Spiritualism when most of the senators are interested in the subject?” Coates asked. “... I know for a fact that there have been spiritual séances held at the White House with President Coolidge and his family.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/52/f8/52f8cce9-f461-4089-92e0-984e957d1a9c/harry_houdini_demonstrating_spiritualist_trickery.png)

1925 magazine spread featuring Houdini exposing psychics' tricks

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In his testimony, Houdini exhibited the skills of a litigator and a showman, treating the House caucus room to a master class on the tricks mediums employed. (“It takes a flim-flammer to catch a flim-flammer,” he told the Los Angeles Times, citing his early vaudeville years, when he’d dabbled in fake spirit communication.) He put the flared end of a long spirit trumpet to the ear of a congressman and whispered into the tube to illustrate how mediums convinced séance guests that spirits had descended in the dark. Houdini also showed legislators how messages from the beyond that mysteriously appeared on “spirit slates” could be concocted in advance, concealed from view and later revealed, all through sleight of hand.

According to Jaher, the crowd listening to Houdini’s commentary included “300 fortune tellers, spirit mediums and astrologers who came to these hearings to defend themselves. They couldn’t all fit in the room. They were hanging from the windows, sitting on the floor, they were in the corridors.” As the Evening Star reported, “The house caucus room today was thrown into turmoil for more than an hour while Harry Houdini, ‘psychic investigator,’ and scores of spiritualists, mediums, and clairvoyants had verbal and almost physical battles over his determination to push through legislation in the District prohibiting fortune-telling in any form.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/47/c8/47c88af1-7a45-474f-aa53-117be6fbe057/houdini_as_ghostbuster_performance_poster.jpeg)

Poster advertising a Houdini lecture debunking Spiritualism

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Houdini’s monomaniacal pursuit of spirit mediums did not sit well with many. On the opening day of the hearings, Kentucky Representative Ralph Gilbert argued that “the gentleman is taking the entire matter entirely too seriously.” Others thought the magician was soliciting Congress’ participation in a witch trial. Jaher explains, “[Houdini] was trying to draw the traditional animus against witchcraft, against these heretical superstitious practices in a predominantly Christian nation, to try to promote a bill that was just a blatant kind of encroachment on First Amendment prerogatives.” Indeed, the heresy implications compelled Spiritualist Coates to say, “My religion goes back to Jesus Christ. Houdini does not know I am a Christian.” Not to be put off his brief, Houdini retorted, “Jesus was a Jew, and he did not charge $2 a visit.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, anti-Semitism repeatedly reared its head as Houdini pressed his case. During the Scientific American contest, Crandon’s husband wrote to Conan Doyle, a champion of the medium, to express his frustration with Houdini’s investigation and the fact that “this low-minded Jew has any claim on the word American.” At the hearings, witnesses and members commented on both Houdini’s Jewish faith and that of the bill’s sponsor, Representative Sol Bloom of New York. One Spiritualist testified, “Judas betrayed Christ. He was a Jew, and I want to say that this bill is being put through by two—well, you can use your opinion; I am not making an assertion.”

It takes a flim-flammer to catch a flim-flammer.

In the end, the bill on mediumship died in committee, its spirit never to reach the full congressional chamber on the other side. The die was cast early in the hearings, when members advised Houdini that the First Amendment protected Spiritualism, however fraudulent its practitioners might be. When Houdini protested that “everyone who has practiced as a medium is a fraud,” Gilbert, a former judge, countered, “I concede all that. But what is the use of us legislating about it?” As for the magician’s desire to see the law protect the public from deception, the congressman resignedly pointed to the old adage “A fool and his money are soon parted.”

Houdini died less than six months after the conclusion of the Washington hearings. He’d aroused so much antipathy among Spiritualists that some observers attributed his mysterious death to the movement’s followers. Just before delivering a series of “hammer-like blows below the belt,” an enigmatic university student who had chatted with the magician before his final show reportedly asked Houdini, “Do you believe the miracles in the Bible are true?”

The magician also received threats to his life from those implicated in his investigation of fraudulent mediums. Walter, a spirit channeled by Crandon, once said in a fit of pique that Houdini’s death would come soon. And Champney, writing under her psychic alias Madame Marcia, claimed in a magazine article penned long after the illusionist’s passing that she had told Houdini he would be dead by November when she saw him at the May hearings.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/99/46/9946a3c2-bc3e-45e3-9c53-02aa87014fe3/houdini_in_handcuffs_1918.jpeg)

A handcuffed Houdini pictured in 1918

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Houdini failed to appreciate that Americans cherish the freedom to be duped. After all, his own contempt for mediums began with his professed hope that some might prove genuine. The fact that none did, he said (perhaps insincerely), did not rule out the possibility that true mediums existed. Houdini also took pains to point out that he believed in God and an afterlife—both propositions others might argue lack proof. As science advanced in Houdini’s time, many did not care to have their spiritual beliefs probed by scientific instruments; they did not believe it was the province of science to validate their beliefs. Theologian G.K. Chesterton, in the 1906 essay “Skepticism and Spiritualism,” said of the two disciplines, “They ought to have two different houses.” The empirical evidence science demands has no role in faith, he argued. “Modern people think the supernatural so improbable that they want to see it. I think it so probable that I leave it alone.”

Perhaps a Halloween séance can still honor Houdini’s legacy of skepticism. Nickell hosted Houdini séances for over 20 years, stopping only a few years ago. No one in attendance actually expected Houdini to materialize. Instead, the gatherings acted as “an important way to remember Houdini,” he says. “You can’t miss the irony of this world-famous magician dying on Halloween and this gimmick of seeing if you can contact his spirit, which you know he knew couldn’t be done. It was all part of a thing to make a point. The Houdini no-show. He was always going to be a no-show.”

“Unless,” Nickell adds, “somebody was fiddling with the evidence.”

Recommended Videos

#History | https://sciencespies.com/history/for-harry-houdini-seances-and-spiritualism-were-just-an-illusion/

No comments:

Post a Comment