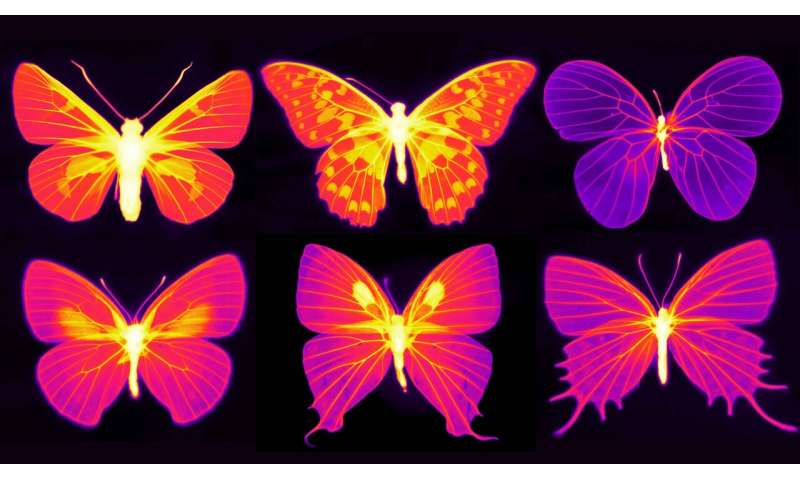

Infrared photographs of butterflies, where brightness correlates with the capability of radiative cooling. Credit: Nanfang Yu and Cheng-Chia Tsai/Columbia Engineering

A new study from Columbia Engineering and Harvard identified the critical physiological importance of suitable temperatures for butterfly wings to function properly, and discovered that the insects exquisitely regulate their wing temperatures through both structural and behavioral adaptations.

Contrary to common belief that butterfly wings consist primarily of lifeless membranes, the new study demonstrated that they contain a network of living cells whose function requires a constrained range of temperatures for optimal performance. Given their small thermal capacity, wings can overheat rapidly in the sun when butterflies cease flight, and they can cool down too much during flight in a cold environment. The study, published online today by Nature Communications, is the first to explore the implications of temperature in shaping the wing structure and behavior of butterflies.

"Butterfly wings are essentially vector light-detecting panels by which butterflies can accurately determine the intensity and direction of sunlight, and do this swiftly without using their eyes," says Nanfang Yu, associate professor of applied physics at Columbia Engineering and co-PI of the study.

The team, which was co-led by Naomi E. Pierce, Hessel Professor of Biology in the department of organismic and evolutionary biology, and Curator of Lepidoptera at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard, used their expertise in biology and optics to make a number of significant discoveries. By carefully removing the wing scales to enable them to peer into the interior of the wings, and by staining the neurons found within the wing, they found that butterfly wings are loaded with a network of mechanical and temperature sensors. The living tissues in the wings are actively supplied by circulatory and tracheal systems throughout the adult lifetime—in the case of painted lady butterflies, for more than three weeks.

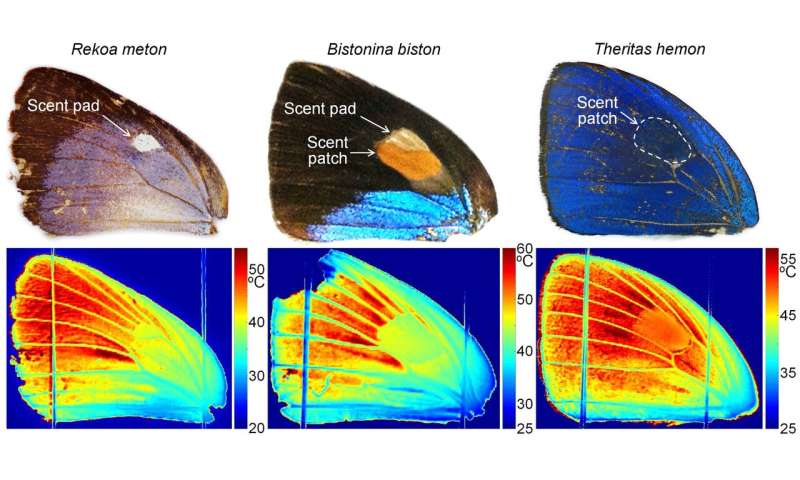

They also discovered a "wing heart" that beats a few dozen times per minute to facilitate the directional flow of insect blood or hemolymph through a "scent pad" or an androconial organ located on the wings of some species of butterflies. "Most of the research on butterfly wings has focused on colors used in signaling between individuals," says Pierce., "This work shows that we should reconceptualize the butterfly wing as a dynamic, living structure rather than as a relatively inert membrane. Patterns observed on the wing may also be shaped in important ways by the need to modulate temperatures of living parts of the wing."

Yu's lab designed a noninvasive technique based on infrared hyperspectral imaging, with each pixel of an image representing one infrared spectrum, that enabled them to make—for the first time—accurate measurements of the temperature distributions over butterfly wings. "This has been difficult to do until now," Pierce notes, "because of the thinness and delicacy of butterfly wings." "This imaging technique enables us to examine physical adaptations that decouple the wing's visible appearance from its thermodynamic properties," Yu adds. "We discovered that diverse scale nanostructures and non-uniform cuticle thicknesses create a heterogeneous distribution of radiative cooling—heat dissipation through thermal radiation—that selectively reduces the temperature of living structures such as wing veins and scent pads."

The effect of this regional and selective enhancement of thermal radiation was amply demonstrated in the team's thermodynamic experiments on butterfly wings. Experimental conditions that mimic the butterflies' natural environment were created in Yu's lab, and allowed the researchers to quantify the relative contributions of several environmental factors to the wing temperature. These included the intensity of sunlight, the temperature of the terrestrial environment, and the "coldness" of the sky, which can serve as an efficient heat sink of thermal radiation from heated wings. The team found that in all simulated environmental conditions, despite diverse visible colors and patterns, the areas of butterfly wings that contain live cells (wing veins and scent pads) are always cooler than the "lifeless" regions of the wing due to enhanced radiative cooling. "The nanostructures found in the wing scales could inspire the design of radiative-cooling materials to cope with excessive heat conditions," says Cheng-Chia Tsai, a Ph.D. student in Yu's group who was lead author of the study.

Temperature distributions on the forewing of three species of Eumaeini butterflies illuminated by sunlight, showing that despite the wings' wide variation in visible coloration and pattern, the temperature of the scent patches, pads, and wing veins that contain living cells is always lower than that of the remaining "non-living" parts of the wings. Credit: Nanfang Yu and Cheng-Chia Tsai/Columbia Engineering

The researchers conducted a series of behavioral studies of living butterflies from six of the seven recognized butterfly families, to investigate responses to simulated sunlight applied to the wings. The team discovered that the insects use their wings to sense the direction and intensity of sunlight—the main source of warmth or overheating—and to respond with specialized behaviors to prevent overheating or overcooling of their wings. For example, all species studied exhibited a relatively constant "trigger" temperature of approximately 40 C (104 F), turning within a few seconds to avoid overheating of wings from a small light spot shone upon them.

Yu and Pierce are now conducting a large-scale systematic optical study of the lepidopteran collections in Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology. These include thousands of individual specimens of hundreds of butterfly species across the entire phylogenetic tree, each specimen with full hyperspectral imaging data taken from the ultraviolet to the mid-infrared. In 1863, Henry Walter Bates, an English naturalist and explorer, wrote about butterfly wings in his book The Naturalist on the River Amazons, "On these expanded membranes Nature writes, as on a tablet, the story of the modifications of species ..." Just like deciphering enigmatic symbols on a tablet, the team hopes to gain a comprehensive understanding of the wing coloration and pattern, which are the results of many (and often conflicting) biological and physical factors: sexual selection, warning coloration, mimicry, camouflage, and thermoregulation.

"Each wing of a butterfly is equipped with a few dozen mechanical sensors that provide real-time feedback to enable complex flying patterns," Yu says. "This is an inspiration for designing the wings of flying machines: perhaps wing design should not be solely based on considerations of flight dynamics, and wings designed as an integrated sensory-mechanical system could enable flying machines to perform better in complex aerodynamic conditions."

The study is titled "Physical and Behavioral Adaptations to Prevent Overheating of the Living Wings of Butterflies."

More information:

Physical and Behavioral Adaptations to Prevent Overheating of the Living Wings of Butterflies, Nature Communications (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-14408-8 , https://nature.com/articles/s41467-020-14408-8

Citation:

Beating the heat in the living wings of butterflies (2020, January 28)

retrieved 28 January 2020

from https://phys.org/news/2020-01-wings-butterflies.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

#Biology | https://sciencespies.com/biology/beating-the-heat-in-the-living-wings-of-butterflies/

No comments:

Post a Comment