In the salt water marshes of southern California, a splashing killifish is easy prey for a hungry shorebird. Like a jerking marionette, the helpless creature shimmies and flashes on the surface of the water. And all the while, hiding deep in its brain, an invisible other quietly pulls the strings.

The puppeteer in question is the super-abundant parasitic flatworm known as Euhaplorchis californiensis. Throughout its life, this one parasite will infect no less than three animals, and a bird's intestine is the final destination it wants to reach.

To get there, the parasite's larva must penetrate a killifish, crawl to its brain and lay down a carpet of cysts, which it then uses to manipulate the host's swimming, sending it thrashing to the surface.

As it happens, infected killifish are preyed on by birds some 10 to 30 times more, and this means that parasites are essentially increasing the amount of resources available to these predators: a relationship we often overlook in the natural world.

The story of the infected fish is a tantalising peak backstage, but it's also a reminder of our sheer ignorance. As the world's climate changes, we can't ignore our parasites any longer.

A parasitic dark matter

Though often hidden to the human eye, parasites are, by some estimates, more than half of all known species on Earth. What's more, they can influence virtually every other free-living animal.

Humans alone play host to nearly 300 types of parasitic worm, and around a third of us are currently infected, whether knowingly or not, with at least one.

They're everywhere, on all sides, maybe even inside. And yet when we picture a classic food chain, how many of us remember the lions, zebras and grass, only to forget their hidden puppeteers?

Compared to free-living species, scientists have collected scant information on parasites. Historically dominated by medical researchers and overlooked by ecologists and conservationists (Darwin himself viewed them as "degenerates"), these organisms are often entirely missing from modern depictions of food chains; even though, in the average ecosystem, parasite–host links actually outnumber predator–prey links.

Only in the last 30 years or so have we realised our mistake.

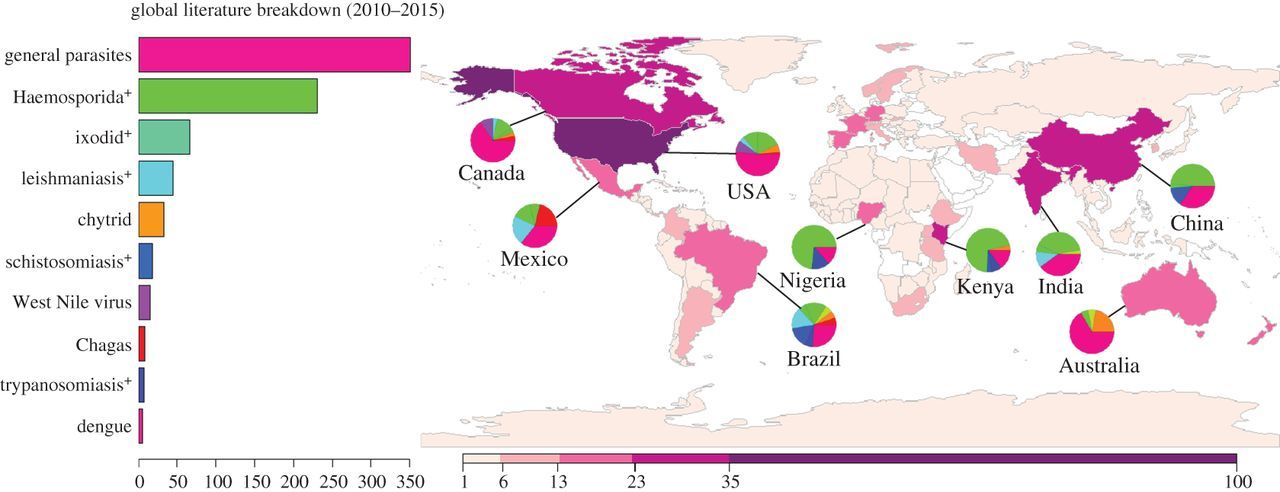

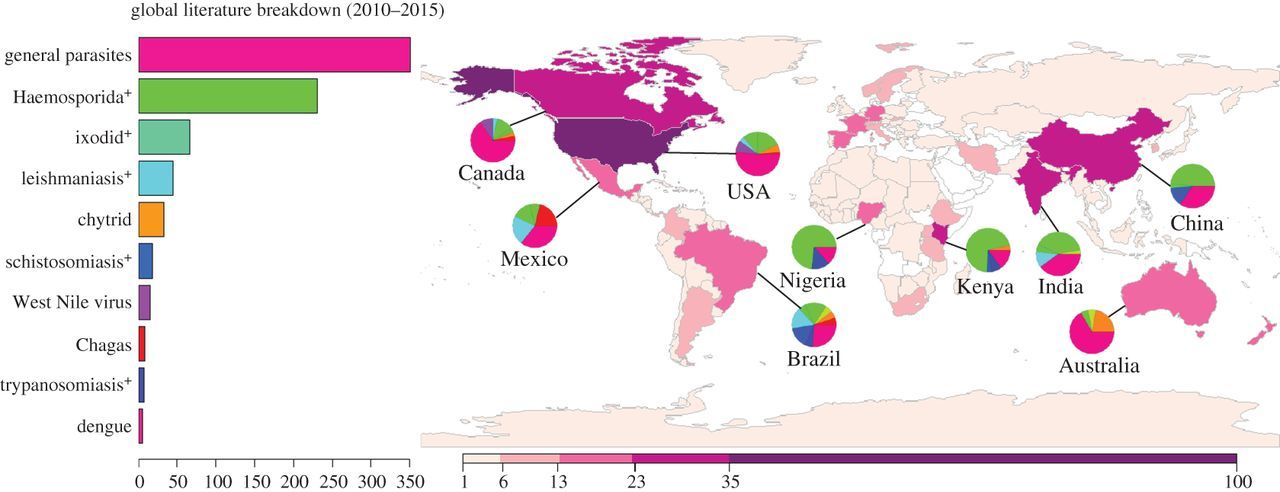

(Cizauskas et al., Royal Society Open Science, 2017)

(Cizauskas et al., Royal Society Open Science, 2017)

Above: Global distribution of parasite climate change research. Research on parasitic species is disproportionately oriented towards human emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), especially in countries where the majority of parasite research occurs.

When parasites like E. californiensis are included in the ecology of California's salt marshes, the classic food web - with a few predators at the top and lots of smaller species on the bottom - is almost literally "turned on its head".

"Essentially," the authors of a 2008 paper explain, "a second web appears around the free-living web, and this completely changes the level of connectivity."

Parasites are thus described as a sort of hidden "dark matter", not only in our ecosystems but also in our models of infection. When Chelsea Wood, a parasite ecologist at the University of Washington, first started researching mass fishing nearly 15 years ago, she told ScienceAlert that we had virtually no idea how this practice might impact resident parasites.

Even now, she adds, when ecosystems are facing unprecedented changes, we have only the foggiest idea how more than half the species on Earth are coping.

Whether acknowledged or not, parasites are key indicators and shapers of healthy communities, influencing the survival and reproduction of whole host populations, causing food web cascades or even epidemics.

Some call them the "omnipresent agents of natural selection", others the "ultimate missing links", still others the "invisible puppeteers".

Whatever the label, it's about time we consider the parasite.

Shooting in the dark

If the history of medical science has taught us anything, Wood argues, it's that the emergence of a new infectious disease can go unnoticed for a long time: the tale of HIV, jumping from primates to humans decades before we recognised it as a global epidemic, is a prime example.

Today, a similar story might be unfolding in our oceans, like a shadow, creeping up the wall behind us.

"We really are just starting to scratch the surface on whether a changing world means rising rates of infectious disease," Wood told ScienceAlert.

In the last few years, scientists have grown ever more concerned that our planet is not only getting warmer, it's also altering the spread and distribution of parasitic diseases.

A recent finding, not yet published by Wood's lab, indicates that from 1978 to 2015, there was a 208-fold increase in Anisakis simplex, a cold water nematode responsible for some 20,000 cases of herring worm disease, usually contracted from eating raw or undercooked seafood.

Whether the trend is due to fishing, climate change or something else, is hard to say for now. In Arctic waters, where this nematode flourishes and climate change is at its worst, we often lack baseline and long-term data, even for the best known parasites and their diseases.

Unfortunately, this means our future projections can often fall short of the rich reality.

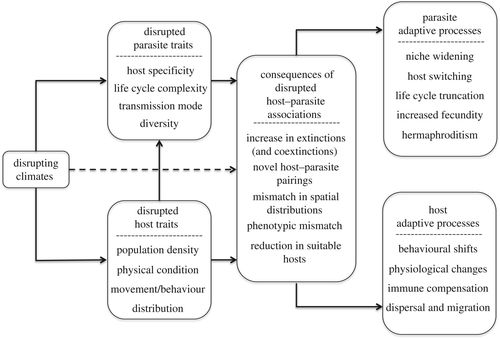

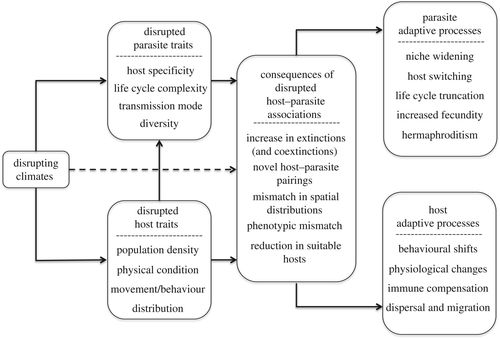

The domino effects of climate change on parasites and their hosts. (Cizauskas et al., Royal Society Open Science, 2017)

The domino effects of climate change on parasites and their hosts. (Cizauskas et al., Royal Society Open Science, 2017)

The latest climate-parasite models are trying to fill-in this blindspot, incorporating not only climate data, but also information on parasitic life cycles, ranges, and opportunities for new hosts.

The initial results suggest that climate change will play a much larger role in disease transfer than we once thought. But what that specifically means for bird-flu, human malaria, A. simplex or other parasitic diseases remains unresolved.

After all, wherever there's few data, there's plenty of doubt. Even Wood, who directly measures parasite prevalence, admits that her research may well contain a sneaking bias. Researchers, you see, tend to pay more attention to those parasites that matter to humans.

"No one cares about parasites that are diminishing into extinction, because they don't hurt people, they don't hurt animals, they don't cause outbreaks, they don't ruin your fish fillet, they don't crawl across your plate at the sushi restaurant," Wood explains.

But that doesn't mean they aren't a vital part of our ecology. While an increase or change in parasite populations will no doubt have serious repercussions for health and agriculture, the flip side may well entail ecological upheaval. Some parasites are certain to flourish, while others will likely decline and go extinct.

A 2017 study on 457 parasite species predicts that five to 10 percent are committed to this fate by 2070, solely from climate-driven habitat loss. The researchers went on to create the first "red list" for parasites.

"Accounting for host-driven coextinctions," the authors write, "models predict that up to 30 [percent] of parasitic worms are committed to extinction, driven by a combination of direct and indirect pressures."

Will the aforementioned E. californiensis number among these wormy losers? Will another invasive parasite take its place? What then will happen to the size, distribution and abundance of killifish? The hungry shorebird? The precious salt marshes? The humans who rely on them?

Gathering answers on the complexities of parasite-host dynamics in all the thousands of mammal and bird species is a nearly impossible task.

As the clock ticks, researchers must act like ghostbusters, hunting down invisible foes, diseases that don't yet exist or have yet to re-emerge in some new unexpected location.

Danielle Claar, a postdoc working in Wood's lab, is studying the effect of El Niño events in the parasite-rich Tropics, because she says these can act as windows into future warming. Others in the team are sifting through countless museum samples and old journals for evidence of the past.

"When you arrive into science you think everyone's got everything figured out," Wood says.

"But as you get deeper in you realise there's so much we don't know. It's staggering."

As the climate crisis takes a firm grip, squeezing some parasites out and holding on to others, what we don't know could very will kill many. And that goes for both parasites and humans alike.

#Environment | https://sciencespies.com/environment/theres-a-huge-ecological-problem-about-to-hit-us-and-nobody-knows-what-will-happen/