An ambitious, first-of-its-kind effort to estimate how many different kinds of trees exist on Earth suggests our planet is teeming with thousands of tree species that still haven't been discovered.

The huge international research effort – involving the work of over 100 scientists – estimates that there are approximately 73,000 tree species in total on Earth, yet so far we've only documented about 64,000 of these.

The remainder, researchers say, equates to roughly 9,200 undiscovered tree species that so far have eluded scientific attention and study.

"We combined individual datasets into one massive global dataset of tree-level data," says quantitative forest ecologist Jingjing Liang of Purdue University from Purdue University.

"Each set comes from someone going out to a forest stand and measuring every single tree – collecting information about the tree species, sizes, and other characteristics. Counting the number of tree species worldwide is like a puzzle with pieces spread all over the world."

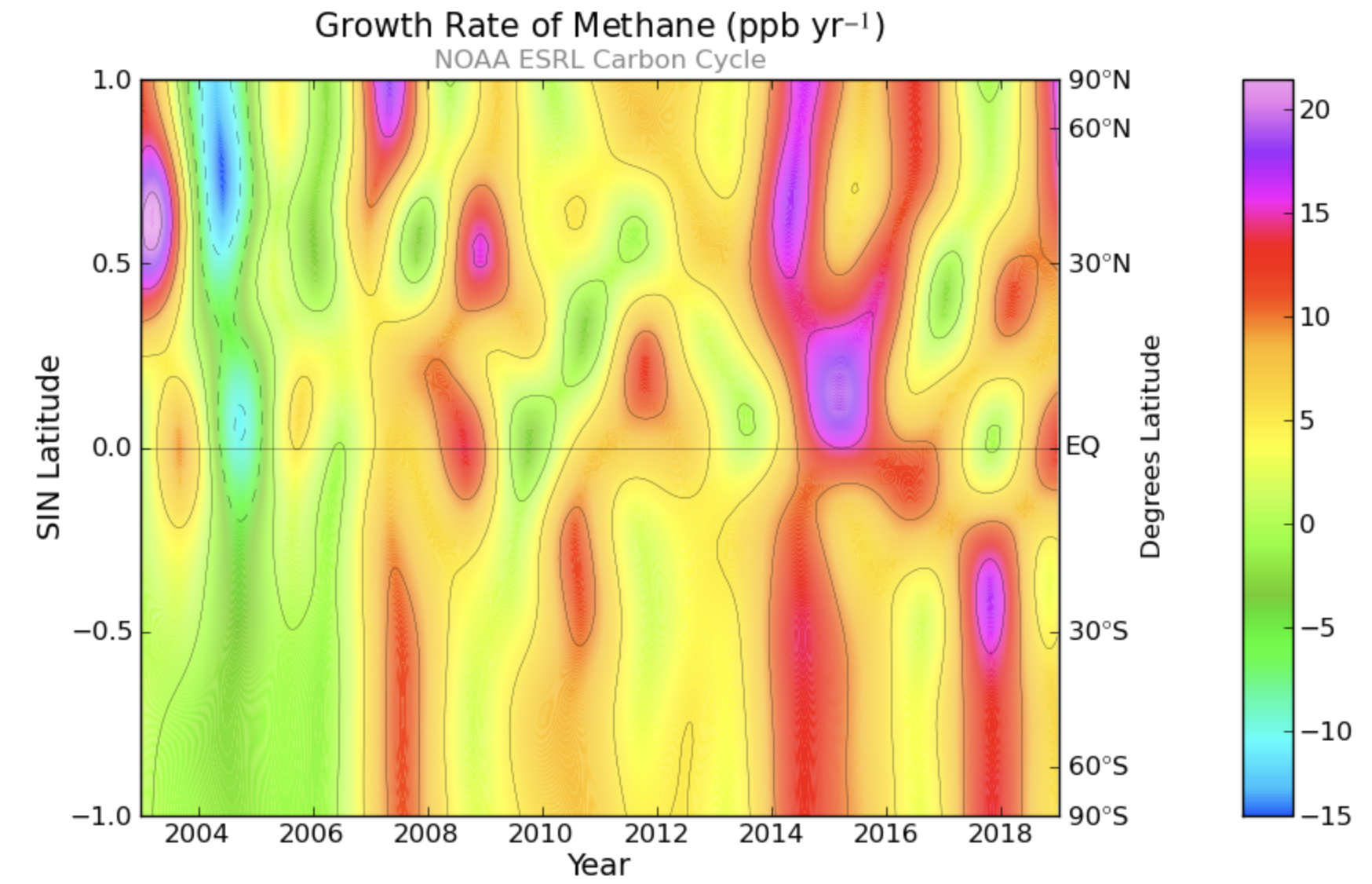

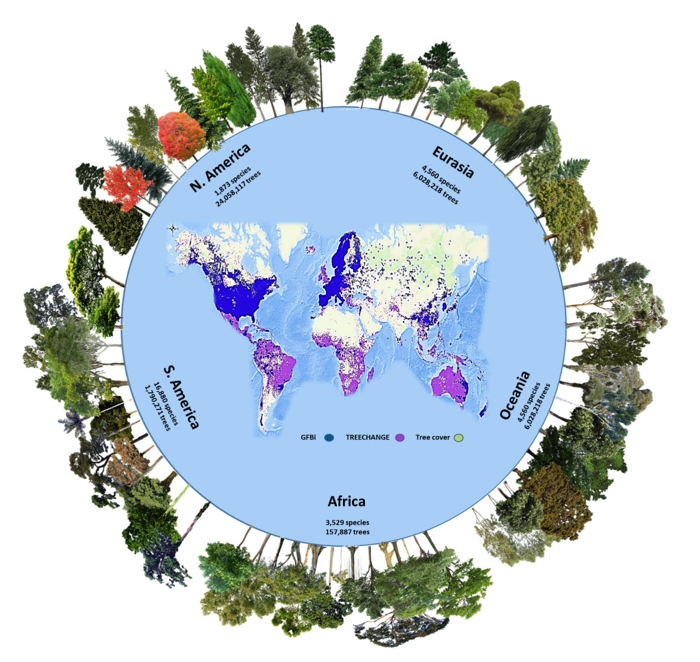

Tree species and individuals per continent in the GFBI database. (Gatti et al., PNAS, 2022)

Tree species and individuals per continent in the GFBI database. (Gatti et al., PNAS, 2022)

In this case, the puzzle consisted of combining two vast tree datasets – one belonging to the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative, of which Liang is the coordinator, and another database called TreeChange.

The data-pooling project, combining many years' worth of ground-sourced tree cataloguing, compiled a global occurrence dataset of tree species across a grid of over nine thousand 100 × 100-kilometer (62 x 62-mile) cells on the planet.

With statistical adjustments accounting for the comparative richness of biomes in different regions, the researchers inferred that there are likely about 9,200 tree species yet to be discovered, although they fully acknowledge this is an estimate based on incomplete data, including areas where the mapping and analysis of tree species is limited.

Nonetheless, the analysis delivers important new insights on the distribution and occurrence of trees around the world.

"Our estimates at continental scales show that roughly 43 percent of all Earth's tree species occur in South America, followed by Eurasia (22 percent), Africa (16 percent), North America (15 percent), and Oceania (11 percent)," the researchers write in their new study.

"More undiscovered species likely occur in South America than any other continent."

The South American species not yet discovered are thought to constitute about 40 percent of all undiscovered species. South America also contains the highest number of rare species (about 8,200 species), and the highest percentage (49 percent) of endemic species not found on other continents.

"Beyond the 27,000 known tree species in South America, there might be as many as another 4,000 species yet to be discovered there," says forest ecologist Peter Reich from the University of Michigan.

"This makes forest conservation of paramount priority in South America, especially considering the current tropical forest crisis from anthropogenic impacts such as deforestation, fires and climate change."

In recent years, that crisis has come into painfully clearer focus, and the researchers say it's imperative that we identify the true diversity of tree life as soon as possible, so as to be able to better shield these threatened species from the changes imperiling them.

"This new global dataset is a significant piece of the puzzle in ecology and biodiversity," says forest researcher Andy Marshall from the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia.

"The better the information, the better we can inform national and international plans for conservation priorities and biodiversity targets and management – potentially saving endangered tree species in the process."

The findings are reported in PNAS.

#Nature | https://sciencespies.com/nature/planet-earth-contains-over-9000-tree-species-yet-to-be-discovered-scientists-say/