The number of wildfires and the amount of land they consume in the western U.S. has substantially increased since the 1980s, a trend often attributed to ongoing climate change. Now, new research finds fires are not only becoming more common in the western U.S. but the area burned at high severity is also increasing, a trend that may lead to long-term forest loss.

The new findings show warmer temperatures and drier conditions are driving an eight-fold increase in annual area burned by high severity fire across western forests from 1985-2017. In total, annual area burned by high severity wildfires -- defined as those that kill more than 95% of trees -- increased by more than 450,000 acres.

"As more area burns at high severity, the likelihood of conversion to different forest types or even to non-forest increases," said Sean Parks, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station and lead author of the new study. "At the same time, the post-fire climate is making it increasingly difficult for seedlings to establish and survive, further reducing the potential for forests to return to their pre-fire condition."

Parks will present the results Wednesday, 9 December at AGU's Fall Meeting 2020. The findings are also published in AGU's journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Scientists have known for years that wildfires are on the rise in the western U.S., coincident with recent long-term droughts and warmer temperatures. Many western states, especially parts of California, have undergone several multi-year droughts over the past four decades, a fact scientists attribute to human-caused changes to the climate. However, it is less clear how fire severity has changed over the past half century.

In the new study, Parks and John Abatzoglou, an atmospheric scientist at the University of California Merced, used satellite imagery to assess fire severity in four large regions in the western U.S. from 1985 to 2017. Rather than analyze the amount of area burned each year, they instead looked at the area burned at high severity, which is more likely to adversely impact forest ecosystems and human safety and infrastructure.

"The amount of area burned during a given year is an imperfect metric for assessing fire impacts," Parks said. "There was a substantial amount of fire in the western U.S. prior to Euro-American colonization, but that fire did not likely have the extreme effects that we're seeing now."

Beneficial fires

Wildfires were historically a common component of many forest ecosystems, especially in dry areas that receive little or sporadic rainfall. Fire was such a common occurrence in some regions that many tree species -- especially certain species of pine -- evolved traits that allow them to not only survive fires but to facilitate their ignition as well.

In the mountainous slopes of California, for example, ponderosa pines, sugar pines and giant sequoias sport thick bark that keeps the living tissue underneath insulated from extreme heat. Some tree species also drop the branches growing closest to the ground, which might otherwise allow fires to climb up into the canopy.

Species like jack pines are so dependent on fire that their seeds are unable to effectively disperse until a passing blaze melts the resinous coating surrounding their cones. And the slender, needle-like leaves of pines dry out more quickly than the broad leaves of deciduous hardwoods, making them excellent kindling.

The catch is these trees evolved to cope with frequent, low-intensity fires. During a severe fire, even the most well-adapted plants can succumb to mortality. If too many trees die, forest regrowth can be impeded by the lack of viable seeds.

"Forest burned at high severity bears the biggest ecological impacts from a fire," said Philip Dennison, a fire scientist at the University of Utah who was unaffiliated with the study. "These are the areas that are going to take the longest to recover, and in many places that recovery has been put into question due to higher temperatures and drought."

A 2019 study authored by Parks found up to 15% of intermountain forests in the western U.S. are at risk of disappearing. In dry regions, such as the southwestern U.S., that number increases to 30% when assuming fires burn under extreme weather.

As western North America continues to reel from the vice-like grip of droughts and increasing temperatures, scientists expect severe fires will become even more common.

"One take home message is that fire severity is elevated in warmer and drier years in the western U.S., and we expect that climate change will result in even warmer and drier years in the future," Parks said.

#Nature | https://sciencespies.com/nature/area-burned-by-severe-fire-increased-8-fold-in-western-us-over-past-four-decades/

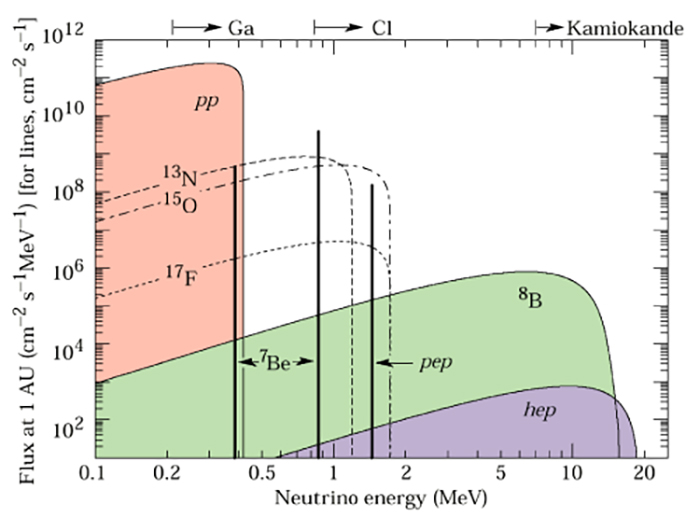

The energy levels of various solar neutrinos. (HERON/Brown University)

The energy levels of various solar neutrinos. (HERON/Brown University)